The federal government wants to save money. Perhaps it should look at the War Hazards Compensation Act (“WHCA”) and use the tools already in its possession to limit monetary reimbursements to insurance carriers for frivolous litigation.

In 2023, insurance carriers received half a billion dollars in annual reimbursements under the WHCA. In 2024, carriers received more than that. Yet, some of those payments are suspect. Essentially, the insurance carriers use the WHCA to fund their litigation against injured workers who seek workers compensation benefits paid under the Defense Base Act (“DBA”), an extension of the Longshore and Harbor Workers’ Compensation Act.

Further, because the U.S. government pays insurance carriers with U.S. tax dollars, focusing on carriers’ problematic reimbursement requests could save the U.S. millions of dollars–millions that could be used to pay for more judges, more support staff, and more claims examiners.

Below, I propose some changes that the Department of Labor could make right now under existing regulations to save tens of millions of dollars–maybe more.

- Don’t bail out insurance carriers who refused reasonable settlement demands. If the carrier ultimately paid more money to a claimant than the claimant’s lowest settlement demand, then deny reimbursement for the litigation costs incurred after the claimant submitted his lowest demand.

- Don’t reimburse carriers for unsuccessful fee litigation.

- Don’t reimburse flat fees or unexplained payments to vendors for their experts, private investigators, and more.

Not only will these actions save the federal government money, they will also reduce litigation at the Office of Administrative Law Judges (“OALJ”). And because the government already has the regulatory authority to open the insurance carrier’s files, the government can already access the information it needs to save money and reduce litigation.

How Much Money Are We Talking About?

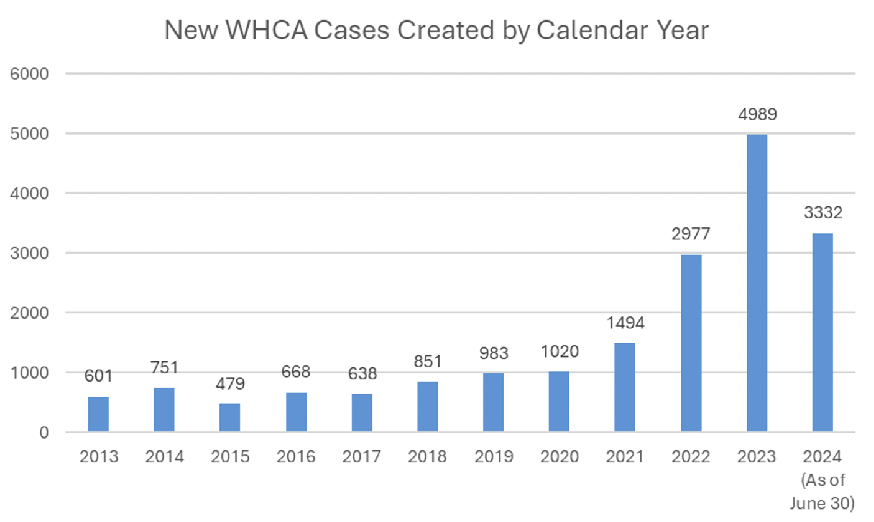

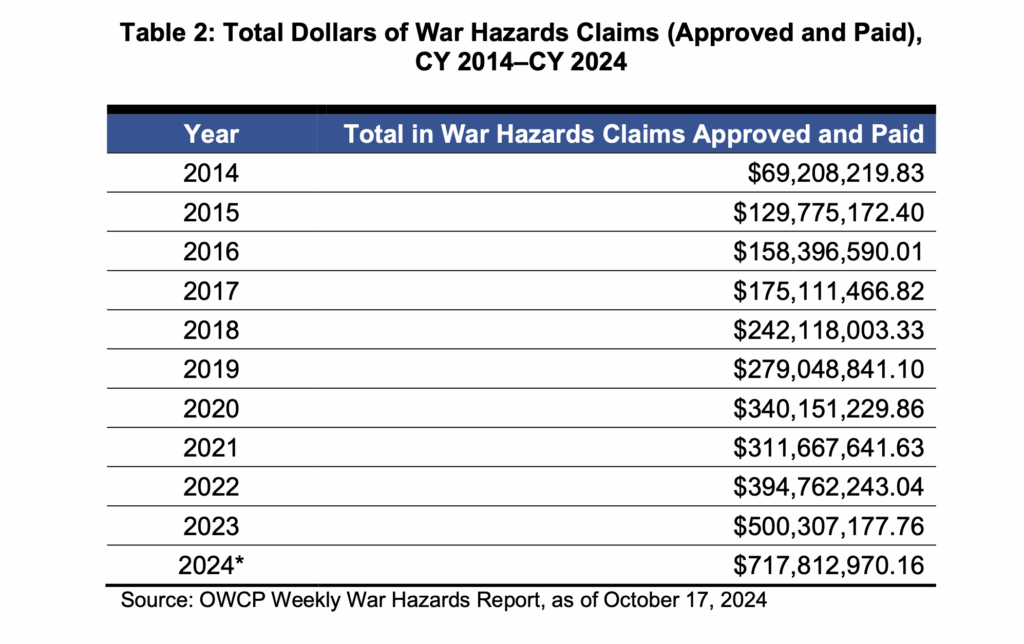

This isn’t chump change. Reimbursements paid to insurance carriers under the WHCA total hundreds of millions of U.S. dollars per year. From January 2014 to June 2024, the Department of Labor’s Division of Federal Employees’ Compensation paid DBA insurance carriers over three billion U.S. dollars.

A WHCA presentation at a July 2024 conference disclosed the amount of money paid to insurance carriers to reimburse them for the workers’ compensation benefits they paid to injured workers:

Based on these figures, the U.S. government paid insurance carriers over half a billion dollars in 2023. To be exact, the U.S. government paid $500,307,177.76 to insurance carriers in 2023. And through six full months of 2024, the U.S. government paid insurance carriers over $450,000,000.

The steady increase in money paid to insurance carriers tracks the number of new WHCA cases filed each year. Remember, WHCA cases arise after the resolution of the injured worker’s underlying DBA claims. The WHCA case is filed by the carrier, not the DBA claimant.

Recently, the Department of Labor’s Office of Inspector General issued a report addressing the WHCA. In OWCP Has Taken Steps to Address the Backlog of War Hazards Claims, the Office of Inspector General revealed the increased monetary reimbursement made to Defense Base Act insurance carriers. According to the May 12, 2025, report, the federal government paid $717,812,970.16 to insurance carriers for the period between January 1, 2024, and October 17, 2024. Three-quarters of a calendar year equaled three-quarters of a billion dollars:

Year after year, payments to insurance carriers increase. But while the OIG’s report focuses on faster payments to insurance carriers, perhaps it should also audit what the federal government is paying for.

Is the Federal Government Subsidizing Defense Base Act Litigation Against Injured Workers?

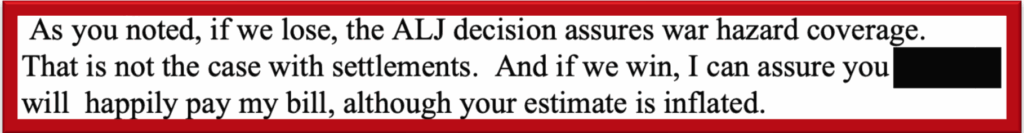

It’s no secret. Insurance carriers and their attorneys know that they suffer absolutely no penalties if they lose the DBA claim to the injured worker if a “war-risk hazard” caused the underlying injury. In other words, insurance carriers win–i.e., get their money and litigation costs back–even when they lose. So, they turn the screws on injured workers and their attorneys send emails like this:

Or this:

The problem is that the dollar amount reimbursed to insurance companies by the government includes money spent fighting legitimate claims or furthering litigation in spite of reasonable settlement demands.

And if the government pays reimbursement requests without careful auditing of insurance carrier expenses, then the government essentially subsidizes insurance carriers to fight and exhaust injured workers. They do so by positing litigation strategies that aren’t supported by current DBA law or the case’s facts. The stall tactics (and ensuing expenses) become part of the litigation strategy–a strategy paid for by taxpayers.

Think about that. The DBA is supposed to be a humanitarian workers’ compensation system designed to help injured workers. Yet, carriers prolong litigation and delay resolution with no fear of repercussions if they lose the DBA claim. If carriers lose the DBA claim all that happens is the insurance carrier writes a check to the injured worker and then turns around and asks the government to repay the full value of that check plus the expenses the carrier incurred engaging in the fight against the injured worker. Blindly repaying claims expenses when a carrier loses the DBA claim does nothing more than promote litigation. Why? Because, like the attorney who drafted the quoted emails recognized, an insurance carrier loss “assures war hazard coverage.”

There are fixes the government could implement to save money in litigation costs. But, first, let’s take a deeper dive into the law…

What is the War Hazards Compensation Act?

Very quickly, DBA benefits are paid to injured and disabled workers. When a “war-risk hazard” event caused the worker’s injury, then the WHCA applies too. Typically, a “war-risk hazard” event is a terrorist attack, like the one pictured above.

Imagine a psychological injury claim. If the event that caused the psychological injury–maybe PTSD–was a “war-risk hazard,” then the insurance company gets back all of the money it paid for benefits, as well as their expenses paid during the DBA claim.

Insurance companies plan for WHCA reimbursement during the course of the DBA claim. WHCA reimbursement claims arise after resolution of the DBA claim. Then, the carrier uses the WHCA reimbursement statute, 42 U.S.C. § 1704(c), to request reimbursement for all benefits and claims expenses paid in the underlying DBA claim.

The reimbursement statute says carriers “shall be entitled to be reimbursed for all benefits so paid or payable including funeral and burial expenses, medical, hospital, or other similar costs for treatment and care; and reasonable and necessary claims expense in connection therewith.”

Notice how the statute uses “shall” with respect to the benefits paid to the injured claimant or on behalf of the injured claimant for disability compensation, medical treatment, and care. But then there is a semicolon. After that semicolon, the statute permits reimbursement for “reasonable and necessary” claims expenses, not all claims expenses.

What are “Claims Expenses” for WHCA Reimbursements?

The WHCA contemplates two types of expenses: allocated claims expenses and unallocated claims expenses. See 20 C.F.R. § 61.104. “Allocated claims expenses” include “payments made for reasonable:”

- Attorneys’ fees (both for both defense and claimant attorneys);

- Court and litigation costs;

- Expenses of witnesses and expert testimony;

- Examinations;

- Autopsies; and

- “Other items of expense that were reasonably incurred in determining liability under the Defense Base Act or other workers’ compensation law.”

Allocated expenses must be itemized and documented according to 20 C.F.R. § 61.101(b). The required documentation must establish:

- The purpose of the payment;

- the name of the payee;

- The date(s) for which payment was made; and

- The amount of the payment.

If the requested reimbursement was a payment for medical benefits, then copies of corresponding reports and invoices must be submitted.

The overarching principle for all claims expenses is simple: the U.S. government will only reimburse “reasonable and necessary” allocated claims expenses. Pursuant to 20 C.F.R. § 61.102, the WHCA and implementing regulations authorize the government to deny reimbursement in whole or in part.

What are “Reasonable and Necessary” Claims Expenses?

The WHCA does not define “reasonable and necessary” claims expenses. Nonetheless, we can glean the meaning from the regulations and OWCP Bulletins (which are memoranda published by the Office of Workers’ Compensation Programs).

First, the government gave us a starting point. It shall “hold the carrier to the same degree of care and prudence as any individual or corporation in the protection of its interests or the handling of its affairs would be expected to exercise under similar circumstances.” See 20 C.F.R. § 61.102(e). In other words, when analyzing the carrier’s actions, the government expects carriers to make reasoned, reasonable, and prudent business decisions.

Because this degree of care appears in a regulation discussing the reimbursement of money, it is safe to say that an appropriate quantum for determining “care and prudence” may be related to the financial liability caused by the carrier’s actions.

Second, 20 C.F.R. § 61.102(e) provides a non-exclusive list of actions which may jeopardize reimbursement in whole or in part:

-

Failed to take advantage of any right accruing by assignment or subrogation . . . due to the inability of a third party, unless the financial condition of the third party or the facts and circumstances surrounding the liability justify the failure;

-

Failed to take reasonable measures to contest, reduce, or terminate its liability by appropriate available procedure under workers’ compensation law or otherwise; or

-

Failed to make reasonable and adequate investigation or [inquiry] as to the right of any person to any benefit or payment; or

-

Failed to avoid augmentation of liability by reason of delay in recognizing or discharging a compensation claimant’s right to benefits.

Third, in years past, the government previously denied reimbursement for “flat fees” associated with allocated claims expenses. The denial for reimbursement of “flat fees” incurred by carriers during the DBA portion of the claim appears to be a blend of 20 C.F.R. § 61.403(b) and 20 C.F.R. § 61.101, extending the flat fee prohibition for claimant attorney fees to insurance carrier fees.

Fourth, OWCP Bulletin 12-01 states that the government “requires” that “the employer/carrier has made only reasonable and prudent efforts in presenting all meritorious defenses against a DBA claim without regard to whether the case is eligible for WHCA reimbursement. An employer/carrier’s inadequate or overly zealous representation in defendant against a DBA claim may be grounds for denying all or some portion of a request for WHCA reimbursement.”

Finally, OWCP Bulletin 12-01 authorizes the government to contact the claimant or the claimant’s legal counsel during the development of any aspect of the reimbursement determination. This is on top of the government’s regulatory authority to examine the insurance carriers records “for the purpose of verifying any allegation, fact or payment stated in the claim.” See 20 C.F.R. 61.103.

WHCA Law in a Nutshell:

Put all this together and what does it mean? It means that insurance carriers do not lose any money when they pay DBA benefits if the injury that caused the DBA injury was a “war-risk hazard.” All of the litigation fees the carriers incurred while fighting injured workers will be reimbursed by the taxpayer, just like expert and private investigator expenses. If the insurance carriers lose their DBA claim–meaning the injured worker wins–then the insurance carrier nevertheless receives WHCA reimbursement. As far as DBA and WHCA claims are concerned, the insurance carriers are playing with house money.

But what if that could change…? What if insurance carriers had a skin in the game with DBA claims…?

Fix #1: Refuse Reimbursements for Amounts Paid in Excess of Claimant’s Lowest Settlement Demand:

Imagine this scenario. A claimant with a psychological injury confirmed by multiple doctors–even the insurance carrier’s doctor–made a final settlement demand for $400,000. The carrier rejected that demand, proceeded to trial, and then lost. The claimant received an order paying ongoing benefits and eventually settled. The total amount paid to the claimant was $1,000,000. Should the government reimburse the carrier the extra $600,000 in excess of the claimant’s $400,0000 settlement demand?

Until now, the government has reimbursed the full amount paid–even when the carrier’s litigation tactics caused the government’s additional monetary liability. The scenario presented in the previous paragraph actually happened.

A better course of action is to deny reimbursement for all amounts exceeding the claimant’s lower settlement demand. Why should the government pay carrier nearly $1,000,000 if carrier could’ve settled the claim and asked for reimbursement of only $400,000? Approving the full $1,000,000 reimbursement subsidizes litigation against claimants and reinforces a carriers’ belief that they can litigate DBA claims without consequences because the government will reimburse all of their expenses under the WHCA.

There is ample regulatory support for allowing the government to refuse reimbursement beyond a claimant’s lowest settlement demand.

When an insurance carrier requests reimbursement, it voluntarily submits to government inquiry regarding “any allegation, fact or payment stated in the claim.” See 20 C.F.R. § 61.103. The government could (and should) take advantage of that authority and investigate whether a carrier handled the underlying DBA claim with “care and prudence.” Cf. 20 C.F.R. § 61.102(e).

To gauge the carrier’s “care and prudence,” the government could focus on settlement negotiations. Typically, a claimant submits a demand first and the parties then exchange numbers back and forth until arriving at a negotiated settlement sum.

Sometimes, the claimant’s settlement demand at the beginning of the claim is completely reasonable. Had the insurance carrier accepted the settlement demand, it would not have incurred additional litigation costs or liability for DBA benefits.

The government could use its authority under 20 C.F.R. § 61.102(e) to require the insurance carrier to provide the dates of each settlement demand and counteroffer, and the amount of each offer and counteroffer. Dates and amounts. That’s not too much to ask.

Essentially, this fix would force the carriers to make reasoned decisions instead of maintaining unwarranted litigation positions. If the carrier weighs its trial and settlement options and decides to move forward with litigation despite the claimant’s reasonable demand, then the carrier has accepted the risk that part of its reimbursement–i.e., the overage–could be jeopardized. Carriers should not receive a WHCA reward after prolonging litigation and ignoring their contractual and statutory duties to pay DBA benefits.

Meanwhile, this fix could also affect how claimants approach their claims. Knowing that a faster resolution would be possible with lower final settlement demands would likely motivate some claimants to submit their final settlement demand sooner in the litigation process.

This fix could also benefit the Office of Administrative Law Judges. There are over 14,000 DBA claims and fewer than eighteen judges adjudicating DBA claims. Motion practice has increased–which is a topic for another post. Decisions could take 2+ years. It is no secret that insurance carriers are choosing to go to trial on more claims, while simultaneously threatening claimants at mediations by highlighting the long wait time for a decision. Moreover, they are repeatedly filing frivolous motions to prevent claimant access to discoverable information–e.g., attack logs, psychological testing data and materials, and Employer representative depositions. If the government denied reimbursement in part when the insurance carrier rejected reasonable settlement demands, then more cases would settle earlier in the litigation process. More voluntary DBA settlements means fewer cases for judges to decide.

In short, Fix #1 (refusing reimbursement for amounts in excess of the claimant’s lowest settlement demand) could result in faster voluntary resolutions, fewer cases going to trial, and less money reimbursed by the government.

Fix #2: Don’t Reimburse Carriers’ Unsuccessful Fee Fights:

Attorneys fees can shift in DBA litigation when certain preconditions are met. See 33 U.S.C. § 928. Sometimes, insurance carriers engage in baffling fee fights for seemingly vindictive reasons. They just want to get even for the lost DBA fight. Yet, all DBA jurisdictions are what we call “fees for fees” jurisdictions. A “fees for fees” jurisdiction allows the claimant’s attorney to submit a supplemental fee petition to cover the time and costs they spend in defending their initial fee petition.

It generally works like this… The insurance carrier failed to pay benefits within 30 days of the employer receiving notice of the employee’s DBA claim. Later, the insurance carrier either loses at the DBA formal hearing or settles the claim. At that time, the liability for fees shifts to the insurance carrier. Let’s say that the sum of the claimant attorney’s fees and expenses costs $70,000.

Instead of paying the fees, the insurance carrier decides to fight. The carrier’s attorneys file objections to the fees, and the administrative law judges must devote judicial resources to this fight. All the while, the insurance carrier pays its attorneys money to fight about paying the claimant’s attorney money. Yet, when the judge issues an order awarding fees, it becomes clear that the insurance carrier spent more money than it saved. The sum of the amount owed to the claimant’s attorney and the amount paid to the defense attorney exceeds the amount deducted (if any) by the administrative law judge. And then, the carrier will lose more money because it must also pay “fees for fees.”

Why not deny reimbursement for these wasteful (and often vindictive) fee fights? The dollar value of the denial could equal the difference between the initial fee petition and the total monetary sum it cost the insurance carrier to engage in the fee fight.

So, let’s say the claimant’s attorney submitted a $70,000 fee petition. The judge ultimately awarded $65,000 for the fee petition for work performed over the life of the claim and another $15,000 in “fees for fees” because the carrier’s decision to litigate the fee petition caused additional litigation. Let’s also say that the defense attorneys’ fees incurred in the fee litigation part of the claim was $15,000. After paying the claimant’s attorney and its own defense attorneys, the insurance carrier spent $95,000 on the attorney fee issue when it could have resolved for $70,000 . In other words, it spent $25,000 more than it needed to spend to resolve the legal issue.

Should the U.S. taxpayer pay the excess for an insurance carrier’s unsuccessful fee fight? So far, the taxpayer has done exactly that. In the prior hypothetical, the taxpayer shelled out the money for the insurance carrier’s unsuccessful fee fight.

Instead of subsidizing insurance carriers’ fee fights–which are often petty disputes that drain judicial resources and incentivize overly zealous litigation–the government should calculate the overall amount saved or lost in a fee fight. If the insurance carrier saved more money than it lost, then no denial is needed. On the other hand, if the cost of the fee fight exceeded the value of the insurance carrier’s savings, then denial is appropriate. A careful and prudent business entity would make a reasoned decision before launching into additional litigation, weighing the potential savings against the potential cost. Cf. 20 C.F.R. § 61.102.

When carriers have a skin in the game and can lose money because of their litigious behavior, that litigious behavior would likely end. Presently, however, the government essentially pays insurance carriers to fight fees and clog up courts because the government does not investigate the reason for and the outcome of the fee fight.

This fix could also benefit OALJ by reducing the number of fee fights the judges must decide. Fewer fee fights means that the scant resources afforded OALJ could be used for other, more meritorious tasks. Again, this could hasten the issuance of Decisions and Orders by giving the OALJ time to address benefits claims instead of refereeing acrimonious fee fights.

So, Fix #2 could result in faster voluntary resolutions of fee litigation, fewer fee petitions and oppositions submitted to OALJ, and less money reimbursed by the government where the cost of the fight exceeded the potential savings.

Fix #3: Don’t Reimburse Flat Fees:

Historically, DFEC would not reimburse flat fees charged by any entity whatsoever. The grounds for the refusal stemmed from 20 C.F.R. § 61.403(b), which states in part: “The Office shall not recognize a contract for a stipulated fee or for a fee on a contingent basis.”

Regulation 61.403 reads like it applies to claimants who file a direct claim for WHCA payments under 42 U.S.C. § 1701, not reimbursement under 42 U.S.C. § 1704. But, I can also see how DFEC could read § 61.403(b) more broadly. After all, in a reimbursement claim, the insurance carrier is the claimant–not the injured worker.

What types of flat fees should DFEC scrutinize?

First, flat fees for defense experts depositions. Some defense experts attempt to charge upwards of $4,000 for depositions, but only if the claimant’s attorney asks for the deposition. Courts routinely reject an expert’s attempt to require prepayment for depositions. DFEC should do the same. Moreover, DFEC could use 20 C.F.R. § 61.103 to require insurance carriers to disclose the hourly rate customarily charged by defense experts and then compare that rate to the total deposition time to reduce any overpayments.

Second, flat fees for expert reports. In the absence of an itemization, flat fees should not be reimbursed. DFEC could require the carrier to produce its contract (or its vendor’s contract) with experts to determine if the expert received a flat fee payment. Moreover, we are now seeing defense experts double-charging for expert reports. In this situation, an expert company pays a contracted expert a flat fee to author a report. Then, the expert company invoices a much higher fee–sometimes more than twice as much–to the insurance carrier’s vendor. Why should DFEC and the U.S. taxpayers pay twice for the same report?

Third, flat fees for expert testimony. Often, we receive invoices purportedly requiring the noticing attorney to pay for four hours (or a full day) of testimony at an exorbitant rate regardless of the expert’s level of experience. Perhaps the deposition will take four hours. Perhaps it only takes one. Why should DFEC and the U.S. taxpayer reimburse an expense associated with an expert’s flat fee for testimony?

Conclusion:

The government can save millions by doing what the existing regulations already permit. The Code of Federal Regulations authorizes the government to scrutinize how the carrier conducted its business during the DBA stage of a claim. Did the carrier act with “care and prudence” to avoid overzealous DBA litigation? Did the carrier “avoid augmentation of liability” by resolving the DBA claim quickly and without costly litigation? Did the carrier refuse to pay flat fees to its vendors and experts–especially exorbitant or double-charged fees? If not, then reimbursement is not owed.

Why not save millions and invest that money in the OALJ for more judges, attorney advisors, and support staff. Further, invest millions in the Office of Workers’ Compensation Programs for my claims examiners. Both are better options for the DBA than subsidizing litigation against injured workers in a humanitarian system designed to protect injured workers.

Here, I proposed three potential fixes, but there are more. Perhaps the government could scrutinize the win/loss percentage for motions filed by insurance carriers repeating the same complaints to incredibly basic litigation demands–e.g., Wmployer representative depositions and test data disclosure. Or perhaps the government could cross-reference expenses amongst multiple files to determine if experts and vendors have charged exorbitant amounts for their services. The government could even evaluate whether a carrier’s continued denial of benefits after the defense medical expert issues a report supporting the injured worker merits an outright denial of reimbursement for expenses paid by the carrier during its fight against the injured worker.

Regulations and statutes exist to save money, reduce litigation, and promote the humanitarian purpose of the Act. The government just needs to use them.