Attorney fees are heavily disputed in Defense Base Act and Longshore and Harbor Workers’ Compensation Act claims. In most cases, the injured worker’s fees shift from the worker to the employer and carrier. When fees shift, then the employer and carrier must pay the worker’s attorney. See 33 U.S.C. § 928. That’s where the arguments start.

Attorney fees are heavily disputed in Defense Base Act and Longshore and Harbor Workers’ Compensation Act claims. In most cases, the injured worker’s fees shift from the worker to the employer and carrier. When fees shift, then the employer and carrier must pay the worker’s attorney. See 33 U.S.C. § 928. That’s where the arguments start.

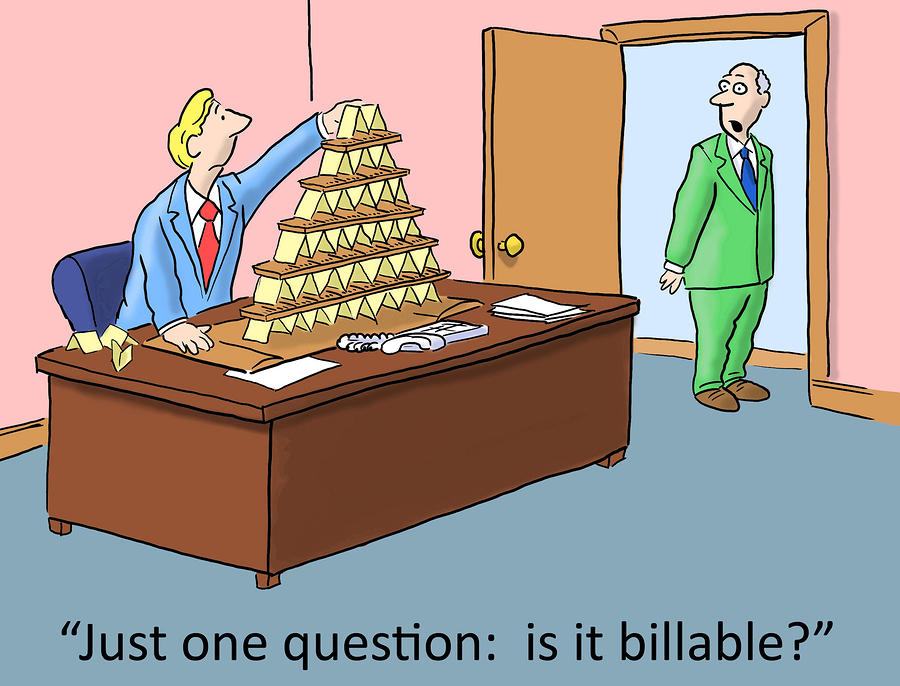

One common argument focuses on the time that a claimant’s attorney spent working on the case. Employers and carriers may argue that the attorney spent too much time on the file (i.e., that attorney spent an unreasonable amount of time litigating their claimant’s case). It should come as no surprise that the claimant attorneys take umbrage with these arguments. Some have suggested that defense attorneys should disclose the hours that they billed while defending a claim before attacking the hours that an injured worker’s attorney spent working on the claim. In fact, there was a chorus of requests for defense attorney bills at the recent Annual Longshore Conference in New Orleans. What’s good for the goose is good for the gander…

A new case from the Supreme Court of Florida provides powerful reasoning in support of the argument that defense attorneys should disclose their bills. See Kelly Paton v. GEICO General Insurance Co., No. SC14-282 (Fla. Mar. 24, 2016) (slip op.). Below, I discuss the Paton holding and how it could be used in fee litigation in DBA and Longshore Act claims.

Paton v. GEICO General Insurance Co:

Paton addresses an attorney fee dispute that developed under Florida insurance law. For this post, the best place to start the Paton discussion is the case’s holding:

We hold that the hours expended by counsel for the defendant insurance company in a contested claim for attorney’s fees filed pursuant to sections 624.155 and 627.428, Florida Statutes, is relevant to the issue of the reasonableness of time expended by counsel for the plaintiff, and discovery of such information, where disputed, falls within the sound decision of the trial court.

What does this mean? It means that the defense attorney should show their hours if they complain about the claimant attorney’s hours. Everyone’s cards are on the table.

Why? Because “the billing records of opposing counsel are relevant to the issue of reasonableness of time expended in a claim for attorney’s fees, and their discovery falls within the discretion of the trial court when the fees are contested.” The Florida Supreme Court reasoned that the “hours expended by the attorneys for the insurance company will demonstrate the complexity of the case along with the time expended, and may belie a claim that the number of hours spent by the plaintiff was unreasonable, or that the plaintiff is not entitled to a full lodestar computation, including a multiplying factor.”

The Requested Records and Claims of Privilege:

The plaintiff attorney in Paton asked the insurance company’s attorney to produce three categories of documents:

- Any and all time keeping slips and records regarding time spent defending [insurer] in the bad faith action in Paton v. GEICO General, Case No.: 09-013697 (12).

- Any and all bills, invoices, and/or other correspondence for payment of attorney’s fees for defending [insurer] in the bad faith action in Paton v. GEICO General, Case No.: 09-013697 (12).

- Any and all retainer agreements between you and/or your respective law firm for defending [insurer] in the bad faith action in Paton v. GEICO General, Case No.: 09-013697 (12).

The insurance company’s attorney cried foul, arguing that the requested information was privileged and irrelevant to the attorney fee dispute.

As for privilege, the defense attorney referenced both attorney-client privilege and the work-product doctrine. The attorney-client privilege is a legal concept that protects certain communications between a client and his or her attorney, and prevents the attorney from being compelled to testify to those communications in court. Essentially, there are four basic elements needed to establish the existence of the attorney-client privilege: (1) a communication; (2) made between privileged persons; (3) in confidence; (4) for the purpose of seeking, obtaining or providing legal assistance to the client.

The work-product doctrine is a separate concept. It protects materials prepared in anticipation of litigation from discovery by opposing counsel. Basically, the law does not want an adversary to obtain documents that reveal another attorney’s mental impression about the case. But, the doctrine is not absolute. If the requesting party can demonstrate that the sought after facts can only be obtained through discovery and that those facts are indispensable for impeaching or substantiating a claim, then the requesting party may obtain the information or documents.

It is the work-product doctrine exception that caught the Florida Supreme Court’s attention. The defense attorney’s billing records were only available to the defense attorney and the insurance company. Yet, the information contained in those records was undoubtedly relevant and discoverable. As such, the Florida Supreme Court denied the defendant insurance company’s claims of privilege, writing:

We . . . conclude that the billing records of opposing counsel are relevant to the issue of reasonableness of time expended in a claim for attorney’s fees, and their discovery falls within the discretion of the trial court when the fees are contested. When a party files for attorney’s fees against an insurance company . . . as occurred here, the billing records of the defendant insurance company are relevant. . . .

Moreover, the entirety of the billing records are not privileged, and where the trial court specifically states that any privileged information may be redacted, the plaintiff should not be required to make an additional special showing to obtain the remaining relevant, non-privileged information. Additionally, even if the amount of time spent defending a claim was privileged, this information would be available only from the defendant insurance company, and the plaintiff has necessarily satisfied the second prong of the test . . . i.e., the information or its substantial equivalent cannot be obtained by other means without undue hardship.

The Scope of Discovery and Relevancy:

Let’s consider, then, the scope of discovery and relevancy, on which the Florida Supreme Court based its holding. These are basic legal concepts that are shared across all U.S. legal systems. As such, for this section, I am going to compare the scope of discovery and relevancy for Florida to the scope of discovery and relevancy in Longshore and Defense Base Act claims.

The scope of discovery in Florida can be found in Florida Rule of Civil Procedure 1.280(b)(1), which states:

Parties may obtain discovery regarding any matter, not privileged, that is relevant to the subject matter of the pending action, whether it relates to the claim or defense of the party seeking discovery or the claim or defense of any other party. . . . It is not ground for objection that the information sought will be inadmissible at the trial if the information sought appears reasonably calculated to lead to the discovery of admissible evidence.

As for relevancy, Florida statutes provide that relevant evidence is defined as evidence that tends to prove or disprove a material fact. Relevancy during the discovery aspect of a claim is very broad.

The scope of discovery in Longshore and DBA claims can now be found in newly enacted Rule 18.51. See 29 C.F.R. § 18.51(a). Rule 18.51 states:

Parties may obtain discovery regarding any nonprivileged matter that is relevant to any party’s claim or defense–including the existence, description, nature, custody, condition, and location of any documents or other tangible things and the identity and location of persons who know of any discoverable matter. . . . Relevant information need not be admissible at the hearing if the discovery appears reasonably calculated to the discovery of admissible evidence.

Relevant evidence is defined by the Rules of Evidence for administrative hearings. See 29 C.F.R. § 18.401. “Relevant evidence means evidence having any tendency to make the existence of any fact that is of consequence to the determination of the action more probable or less probable than it would be without the evidence.”

Clearly, the scope of discovery and the definition of “relevant evidence” in Florida and the DBA and Longshore Act is nearly identical in form, substance, and spirit. Consequently, an administrative law judge in a Longshore and Defense Base Act claim may find the Paton decision persuasive and allow discovery of the defense attorney’s invoices.

My Two Cents:

I would like administrative law judges to apply the Florida Supreme Court’s reasoning to certain attorney fee disputes in Longshore and Defense Base Act claims. If the defense attorney objects to fees, stating that the time spent by the claimant’s attorney in the prosecution of his client’s claim was not reasonable, then the defense counsel’s invoices should be discoverable. The parties should be able to make arguments after all the cards are on the table.

Some practitioners may cite the U.S. Supreme Court’s admonition in Hensley v. Eckerhart, 461 U.S. 424 (1983), that fee disputes should not spawn “a second major litigation.” This argument should fall flat. The “reasonable time” argument starts with the defense attorney, not the claimant’s attorney.

Pragmatically, I think that the Paton case may result in fewer attorney fee disputes. Employers and carriers may think twice about authorizing their attorney to make “reasonable time” arguments when the defense attorney has to disclose their time, too. Disclosure would take the bark and bite out of a “reasonable time” argument. Consequently, time sheet disclosure by all parties may be the most reasonable way to prevent attorney fee disputes from spawning a second major litigation.

Again, just my two cents.