The Longshore and Harbor Workers’ Compensation Act includes a statute of limitations–a time limit for filing a claim. The Defense Base Act (“DBA”) is an extension of the Longshore Act, and it applies the same statute of limitations. The statute provides a one-year window for filing traumatic injury claims and a two-year window for filing occupational disease claims.

The Longshore and Harbor Workers’ Compensation Act includes a statute of limitations–a time limit for filing a claim. The Defense Base Act (“DBA”) is an extension of the Longshore Act, and it applies the same statute of limitations. The statute provides a one-year window for filing traumatic injury claims and a two-year window for filing occupational disease claims.

Recently, I have seen a glut of motions for partial summary decision arguing that the statute of limitations ran against injured Kosovar, Macedonians, Bosnians, and other foreign nationals, who filed a claim more than two years after they first received a mental health diagnosis. If the assigned administrative law judge grants the motion, then the claimant may only pursue medical benefits. Often, these motions are filed early in a claim, soon after a claimant’s deposition, when additional discovery is still needed.

These injured third country nationals have been paying out of their own pocket for medical treatment related to injuries they sustained at work. They are unaware that they have a cause of action against the employer for both indemnity and medical benefits under the DBA. In fact, these third country nationals are unaware of the existence of the DBA because their employers did not post the statutorily mandated Form LS-241, which is a notice to employees that they have workers’ compensation rights.

That begs the question: Can an employer’s willful disobedience of its obligation to notify employees that they have rights under the DBA form the basis for equitable tolling of the Longshore Act and DBA’s statute of of limitations?

I contend that equitable tolling exists in Longshore Act and Defense Base Act claims, and it should apply when employers fail to post notices of workers’ compensation rights. Consider the following:

- The Longshore Act’s statute of limitations, which applies to the DBA, is a federal statute of limitations.

- Equitable tolling customarily applies to federal statutes of limitations.

- The Longshore Act is a remedial and humanitarian Act.

- The Longshore Act requires employers to post notices to employees–the Form LS-241–informing them of their workers’ compensation rights and the procedure for pursuing those rights.

- Failure to conspicuously post and maintain the Form LS-241 is an “extraordinary circumstances,” or an “extraordinary obstacle,” that hides the existence of workers’ compensation remedies from injured workers.

- Equitable tolling applies to other federal remedial and humanitarian Acts like Title VII, the ADEA, and the FLSA when employers fail to post notices to employees of their labor law rights and the procedure for pursuing those rights.

- If equitable tolling applies to other federal statutes of limitations when an employer fails to post notices to employees, then so too should equitable tolling apply to the Longshore Act’s federal statute of limitations for the exact same conduct.

- At the very least, the possible existence of equitable tolling should prevent a court from granting a motion for partial summary decision that an injured worker’s claim for disability benefits is untimely because equitable tolling is a fact-intensive inquiry.

Make no mistake, this is an increasingly important issue that will spark years of litigation in many, many claims.

Section 13 of the Longshore Act:

Section 13 contains the statute of limitations for Longshore Act claims. See 33 U.S.C. § 913 (2012). The Longshore Act and the Defense Base Act are federal workers’ compensation systems. Therefore, Section 13 is a federal statute of limitations.

Generally, the statute of limitations for a traumatic injury is one year. Id. at § 913(a). The time for filing shall not begin to run until the employee is aware or “by the exercise of reasonable diligence should have been aware” of the relationship between the injury and the employment. Id. Occupational diseases receive a longer statute of limitation period: two years. Id. at § 913(b). The statute of limitations for occupational diseases “shall be timely if filed within two years after the employee . . . becomes aware, or in the exercise of reasonable diligence or by reason of medical advice should have been aware, of the relationship between the employment, the disease, and the disability . . . .” Id.

The statute of limitations can be tolled. In fact, there are express tolling provisions in Section 13 and elsewhere in the Longshore Act. The statute does not run against mentally incompetent individuals without a guardian or authorized representative. Id. at § 13(c). The same holds true for minors. Id. The time for filing a Longshore Act claim is also tolled where “recovery is denied to any person, in a suit brought at law or in admiralty to recover damages in respect of injury . . . on the ground” that the person should have pursued a Longshore act claim. Id. at § 13(d). In that scenario, the time for filing begins to run only from the date of termination of such suit.

Another tolling provision is located in Section 30(f) of the Longshore Act. See 33 U.S.C. § 930(f) (2012). The Longshore Act requires the use of practice-specific forms. See, e.g., 33 U.S.C. §§ 914, 930, 934 (2012). For example, an employer with knowledge of an injury must file a Form LS-202 when they have notice or knowledge of an employee’s injury. See 33 U.S.C. § 930(a). If the employer or carrier “fails, neglects, or refuses” to do so, then the Section 13(a) statute of limitations is tolled until the employer files the Form LS-202. Id. at § 930(f).

Yet another statute of limitations tolling provision appears in Section 8(13)(D). See 33 U.S.C. § 908(13)(D). There, the time for filing a notice under Section 12, and the time for filing a claim for compensation under Section 13, shall not begin to run until the employee has “received an audiogram, with the accompanying report thereon, which indicates that the employee has suffered a loss of hearing. Id.

Section 34 of the Longshore Act:

The Longshore Act, like many labor laws, contains a requirement that employers post a notice to its employees of their rights available under the Act. Section 34 of the Longshore Act states:

Every employer who has secured compensation under the provisions of this chapter shall keep posted in a conspicuous place or places in and about his place or places of business typewritten or printed notices, in accordance with a form prescribed by the Secretary, stating that such employer has secured the payment of compensation in accordance with the provisions of this chapter. Such notices shall contain the name and address of the carrier, if any, with whom the employer has secured payment of compensation and the date of the expiration of the policy.

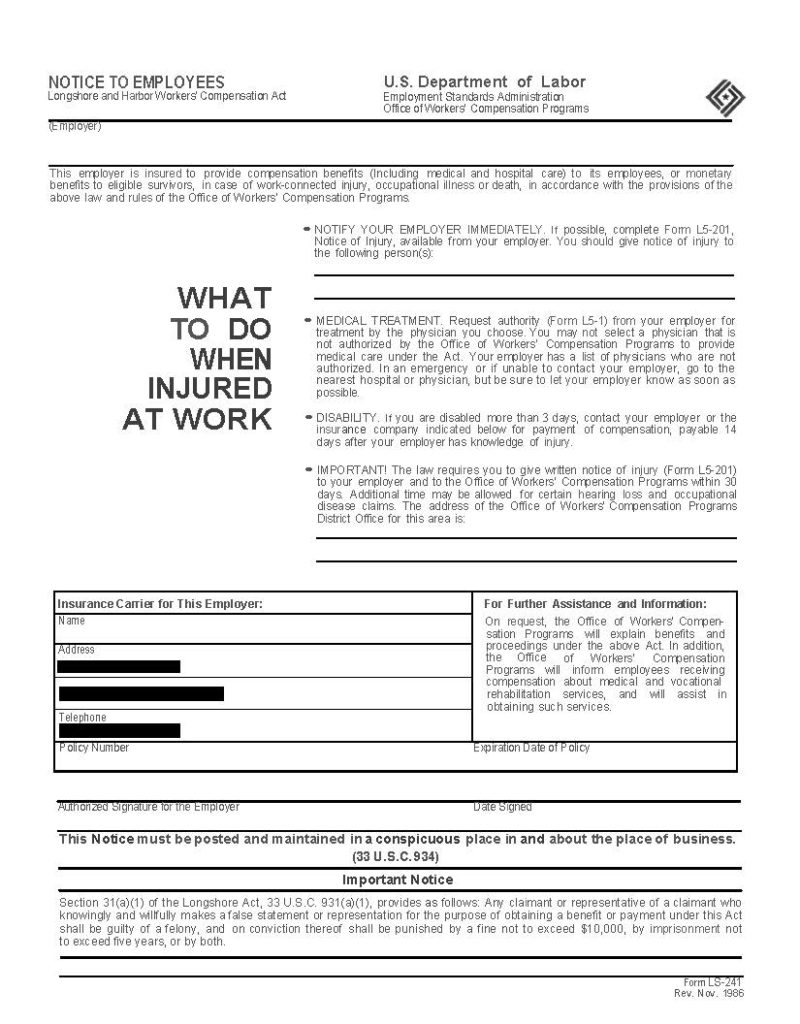

What is the Form LS-241, Notice to Employees?

The form prescribed by the Secretary is the Form LS-241—also called the Notice to Employees. The Form LS-241 does a number of things: (1) assures employees that the employer obtained workers’ compensation insurance (2) provides a contact person for reporting injuries; (3) provides injured workers with guidance on pursuing Section 7 medical treatment; and (4) provides injured workers with guidance on pursuing Section 8 disability benefits. Further, in bold letters, the Form LS-241 states: “This Notice must be posted and maintained in a conspicuous place in and about the place of business.” Finally, the largest font on the Form LS-241 is an all-caps call to action: WHAT TO DO WHEN INJURED AT WORK.

What Does the Form LS-241 Look Like?

Because the Form LS-241 is provided by the insurance carrier to its insureds, there is not a copy of the Division of Longshore and Harbor Workers’ Compensation webpage. Here is what a Form LS-241 looks like:

Equitable Tolling and Federal Statutes of Limitations:

Equitable tolling allows a litigant to avoid the harsh results of a statute of limitations. Essentially, the time limit in the statute would not start to run because of certain events that may have prevented the pursuit of a cause of action. See, e.g., Young v. United States, 535 U.S. 43, 49-50 (2002).

Limitations periods are customarily subject to equitable tolling. “Congress is presumed to incorporate equitable tolling into federal statutes of limitations because equitable tolling is part of the established backdrop of American law.” Lozano v. Montoya Alvarez, 572 U.S. 1, 11 (2014).

Equitable tolling does not apply to time limits that are jurisdictional. To be sure, the Longshore Act does contain time limitations that are jurisdictional, like Section 21’s 60-day filing period. See 33 U.S.C. § 921 (2012). Section 21(c) actually “uses the word ‘jurisdiction’ in the statute.” Adkins v. Director, OWCP, 889 F.2d 1360 (4th Cir. 1989); see also Pittston Stevedoring Corp. v. Dellaventura, 544 F.2d 35, 44 (2d Cir. 1976).

Section 13, however, is not a jurisdictional limitations period. Failure to timely file a claim does not rob an administrative court of jurisdiction. The Section 13 statute of limitations only applies to Section 8 compensation benefits. Marshall v. Pletz, 317 U.S. 383, 389-90 (1943). It does not apply to medical benefits. Id. As such, a “medical-only” claim may still be litigated even if the Section 13 time period for filing a claim legitimately expired. Siler v. Dillingham Ship Repair, 28 BRBS 38 (1994). Because Section 13 does not contain a jurisdictional time limit, and because cases may proceed to formal hearing even if the statute of limitations has run against a claim for Section 8 compensation benefits, it is a federal statute to which equitable tolling may apply.

A litigant must establish two elements to prove an entitlement to equitable tolling: “(1) that he has been pursuing his rights diligently, and (2) that some extraordinary circumstances stood in his way and prevented timely filing.” Holland v. Florida, 560 U.S. 631, 649 (2010); see also Zerilli-Edelglass v. New York City Transity Auth., 333 F.3d 74, 80-81 (2003). The two elements are separate prongs, and a litigant must establish both. Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin v. U.S., 136 S.Ct. 750, 756 (2016). The “extraordinary circumstances” prong can include an “external obstacle”—i.e., “some extraordinary circumstances [that] stood in his way.” Id. at 756 (emphasis added) (quoting Holland, 560 U.S. at 649).

Diligence is a fact-by-fact inquiry. In my view, the quantification of a third country national’s diligence should consider the claimant’s education, mother tongue, limited access to knowledgable DBA attorneys, limited access to a DBA form sitting thousands of miles away on another continent, etc.

The focus of this post, however, is not the diligence of a DBA claimant. Instead, I am focusing on the “extraordinary circumstances” or “external obstacles” created by employers that do not post the Form LS-241, Notice to Employees, and the existence of a remedy to the statute of limitations problem the recalcitrant employer created for its employees.

Employers are Required to Post the Form LS-241, and Failure to Do So Creates “Extraordinary Circumstances” or “External Obstacles”:

How many different ways does an employer need to be told to follow the law?

First, and as explained above, the Longshore Act contains a statutory mandate that employers post the Form LS-241, Notice to Employees. Posting the Form LS-241 is not an aspirational goal. It is a requirement. Employers “shall” post. End of story. See 33 U.S.C. § 934.

Second, when an insurance company offers DBA insurance to an employer, the insurance company provides the employer with the actual Form LS-241. The insurance policy actually comes with the Form LS-241. The cover letter accompanying the policy and the Form LS-241 includes language that tracks Section 34 of the Longshore Act, nearly verbatim. In other words, the insurance company (or broker) specifically instructs the employer to conspicuously post and maintain the Form LS-241.

Third, to get a government contract, employers must affirm in that contract that they will adhere the Longshore Act and the DBA. The contracts awarded to employers to perform work on overseas bases contain Federal Acquisition Regulations. One of those regulations is known as FAR 52.228-03. The text of FAR 52.228-03 can be found in the Code of Federal Regulations. See 48 C.F.R. § 52.228-3 (2020). FAR 52.228-03 requires contracting companies to “[a]dhere to all other provisions of the Longshore and Harbor Workers’ Compensation Act as extended by the Defense Base Act, and Department of Labor regulations at 20 CFR Parts 701 to 704.” Id. So, to get the lucrative government contract, the employer must affirm that it will adhere to all Longshore Act and DBA provisions, including the Section 34 posting requirement.

Employers are told three different ways to post the Form LS-241. They are told by the U.S. Code, their insurance company, and their own government contracts to post the notice to employees of their rights and responsibilities. In exchange for government dollars, employers affirmatively agree to post the Form LS-241 because doing so is a provision of the applicable law. When employers fail to follow this simple notice posting requirement, then they create an “extraordinary circumstance” or “external obstacle.”

The failure of an employer to post the required notice should be grounds for equitable tolling, like it is in other areas of the law.

Equitable Tolling Under Title VII for Failure to Post Notices:

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, and national origin. See 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq. (2012). Title VII contains a notice provision: “Every employer . . . shall post and keep posted in conspicuous places upon its premises where notices to employees . . . are customarily posted a notice . . . setting forth excerpts from or, summaries of, the pertinent provisions of this subchapter and information pertinent to filing of a complaint.” See 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-10 (2012). Title VII’s notice provision is substantially similar to the Longshore Act’s notice provision. Compare 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-10, with 33 U.S.C. § 934.

Equitable tolling applies to late-filed Title VII lawsuits. Zipes v. Trans World Airlines, Inc., 455 U.S. 385, 398 (1982). Failure to comply with EEOC posting requirements may provide a basis for equitable tolling. Mercado v. Ritz-Carlton San Juan Hotel, Spa & Casino, 410 F.3d 41, 46-47 (1st Cir. 2005). When a party asserts that “no informational notices were posted and that they had no knowledge of their legal rights until informed by their attorney, they have met the threshold requirements for avoiding dismissal of their Title VII suit.” Id. at 48. Factual development is needed to determine if equitable tolling is available. Id. at 49. Title VII is rooted in remedial and humanitarian principles. E.E.O.C. v. Western Publ’g Co., Inc., 502 F.2d 599, 603-04 (8th Cir. 1974).

Equitable Tolling Under the ADEA for Failure to Post Notices:

The Age Discrimination in Employment Act prohibits discrimination based on an employee’s age. See 29 U.S.C. § 621 et seq. (2012). The ADEA contains a notice provision similar to the Longshore Act’s Section 34. The ADEA’s notice provision states: “Every employer, employment agency, and labor organization shall post and keep posted in conspicuous places upon its premises a notice to be prepared or approved by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission setting forth information as the Commission deems appropriate to effectuate the purposes of this chapter.” See 29 U.S.C. § 627 (2012). Courts have held that failure to post the requisite notice will equitably toll the time limit for filing ADEA charges within 180 days of the alleged discrimination. Kale v. Combined Ins. Co. of Am., 861 F.2d 746, 753 (1st Cir. 1988) (discussing competing interests in the equitable tolling inquiry); DeBrunner v. Midway Equip. Co., 803 F.2d 950, 952 (8th Cir. 1986) (“Equitable tolling arises upon some positive misconduct by the party against whom it is asserted.”); McClinton v. Alabama By-Products Corp., 743 F.2d 1483 (11th Cir. 1984). The ADEA is remedial and humanitarian legislation. Dartt v. Shell Oil Co., 539 F.2d 1256, 1260 (10th Cir. 1976).

Equitable Tolling Under the FLSA for Failure to Post Notices:

The Fair Labor Standards Act, 29 U.S.C. § 201 (2012) et seq., has posting requirements, too. See 29 C.F.R. § 516.4 (2020) (“Every employer . . . shall post and keep posted a notice explaining the Act, as prescribed by the Wage and Hour Division, in conspicuous places in every establishment where such employees are employed so as to permit them to observe readily a copy.”). Courts have identified a split between circuit and district courts regarding the tolling effect of an employer’s failure to post the notice. See, e.g., Ramirez v. Rifkin, 568 F. Supp. 2d 262, 269-70 (E.D. N.Y. Jun. 23, 2008) (listing cases). Some courts have held that failure to post the required labor law posters equitably tolled the statute of limitations. See, e.g., Asp. v. Milardo Photography, Inc., 573 F. Supp. 2d 677, 698 (D. Conn. Aug. 28, 2008) (“Instead, the trend regarding the failure to post FLSA notices is more flexible and permits equitable tolling where the plaintiff did not consult with counsel during his employment and the employer’s failure to post notice is not in dispute.”). The Second Circuit—which is the precedential circuit in nearly all third country national claims—has not taken a position regarding equitable tolling. Ramirez, 568 F. Supp. 2d at 269. Failure to post has, however, been grounds for denial of a motion of summary decision due to the existence of genuine issues of material fact regarding the application of equitable tolling. Id. at 270-71; see also Asp, 573 F. Supp. 2d at 698 (“The Plaintiffs should not be penalized for not being aware of a right that they had no means of knowing.”). The FLSA is a remedial and humanitarian Act. Valerio v. Putnam Assocs. Inc., 173 F.3d 35, 42-43 (2d Cir. 1999).

Equitable Tolling Under State Workers’ Compensation Systems for Failure to Post Notices:

Although state workers’ compensation systems fall outside of the presumption that equitable tolling applies to federal statutes of limitation, the existence in state workers’ compensation systems of equitable tolling for failure to post notices of legal rights buttresses the argument that equitable tolling should apply to Longshore Act claims. For example, Missouri requires employers to post notices that notify employees of their workers’ compensation rights. See Mo. Rev. Stat. § 287.127 (2018). Employers that do not “substantially comply” with notice posting requirements may lose their statute of limitations defense until the employee has actual knowledge of the information required by the notice statute. Parrott v. HQ, Inc., 907 S.W.2d 236, 241-42 (Mo. Ct. App. 1995). And in California, the failure to post notices informing employees of their rights under workers’ compensation law was grounds for tolling the one-year claim filing period. See Pugh v. Workers’ Comp. Appeals Bd., 2008 WL 4767352 (Cal. Ct. App. Nov. 3, 2008) (unpublished) (“The notice that the County failed to post informs the employee” of their rights and responsibilities).

There is Little Guidance in Precedential Longshore Caselaw About Equitable Tolling–as Opposed to Laches:

Most foreign national DBA claims are administered in New York. Therefore, opinions from the Supreme Court and the Second Circuit Court of Appeals are precedential. Neither of those courts have addressed the existence of equitable tolling in Longshore Act claims. Therefore, the fallback should be that equitable tolling is presumed to exist.

But, I have to mention a footnote from a published Benefits Review Board decision, and the subsequent unpublished Ninth Circuit decision that followed. V.M. [Morgan] v. Cascade General, Inc., 42 BRBS 48, 52, n.5 (2008), aff’d mem., 388 F. App’x 695 (9th Cir. 2010) (unpublished). In the Board’s decision, the Board made the following statement in a footnote:

As the Act contains a specific statutory period for filing a claim at Section 13, and includes specific grounds for tolling the limitations period pursuant to Section 13(c), 33 U.S.C. § 913(c), on the basis of mental incompetence and minority, the doctrine of equitable tolling is not applicable to claims under the Act.

The Board’s footnote appears to incorporate a canon of statutory interpretation called expressio unius est exclusio alterius—meaning the expression of one thing excludes others. The idea appears to be that because Section 13 mentions events that expressly toll the statute of limitations, all other possible events that could toll the statute of limitations must be excluded.

I don’t think that is right. The expressio unius canon “applies only when ‘circumstances support[] a sensible inference that the term left out must have been meant to be excluded.’” N.L.R.B. v. SW Gen., Inc., 137 S.Ct. 929, 940 (2017) quoting Chevron U.S.A. Inc. v. Echazabal, 536 U.S. 73, 81 (2002). Congress did not intend Section 13 to be the sole statement regarding the existence of tolling. In fact, Congress included other tolling provisions in the Longshore Act, which means that Section 13 is not the end-all-be-all for tolling. See, e.g., 33 U.S.C. § 908(13)(D) (tolled until receipt of an audiogram and report); 33 U.S.C. § 930(f) (tolled until Employer files the Form LS-202). Courts have consistently found other reasons to toll the statute of limitations. See, e.g., Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Co. v. Director, OWCP, 583 F.2d 1273, 1280-81 (4th Cir. 1978) (tolled for misdiagnosis). “Like other canons of statutory construction, [expressio unius] is only an aid in the ascertainment of the meaning of the law, and must yield whenever a contrary intention on the part of the lawmaker is apparent.” Springer v. Government of Philippine Islands, 277 U.S. 189, 206 (1928).

Summary Decision Should Not Be Granted in DBA Claims When Equitable Tolling Possibly Applies:

Tolling is a fact-intensive inquiry. “Summary judgement is often inappropriate when tolling is at issue . . . .” Cocke v. Merrill Lynch & Co., Inc., 817 F.2d 1559, 1561 (11th Cir. 1987) (ADEA). Summary decision is granted only when there is a”no genuine dispute as to any material fact.” See 29 C.F.R. § 18.72 (2015). “Inadequate notice has been cited by the Supreme Court . . . as a ground for invoking equitable tolling.” Ortega Candelaria v. Orthobiologics LLC, 661 F.3d 675, 680 (1st Cir. 2011) (citing Baldwin Cnty. Welcome Ctr., 466 U.S. 147, 150 (1984) (per curiam)). Tolling is appropriate where defendants failed to provide notice of the right to bring a cause of action. Veltri v. Building Serv. 32B-J Pension Fund, 393 F.3d 318, 325 (2d Cir. 2004). Grants of summary decision where tolling may apply have been reversed by courts in the past. See, e.g., Ortega Candelaria, 661 F.3d 681-82; Santos v. U.S., 559 F.3d 189, 195-98 (3d Cir. 2009); Seitzinger v. Reading Hosp. and Med. Ctr., 165 F.3d 236, 241 (3d Cir. 1999). Evidentiary hearings are appropriate when “equitable tolling arises upon some positive misconduct by the party against whom it is asserted.” Canales v. Sullivan, 936 F.2d 755, 758 (2d Cir. 1991) (vacating dismissal and remanding for an evidentiary hearing in late-filed Supplemental Security Income appeal).

Because tolling is a fact-intensive inquiry, summary decision for statute of limitations issues should be denied in DBA claims at least while the parties pursue written discovery and employer depositions regarding notice posting issues. I have addressed this notice issue with a number of employees for a particular large employer. No matter the individual employee’s country of origin–Bosnia, Kosovo, Macedonia, or the United States–all of the employees say the same thing: the employer never posted the Form LS-241 anywhere. These employees never saw the Form LS-241 even though there were many different places where employer could have conspicuously posted and maintained the Form LS-241–e.g., common areas, dining facilities, work trailers, machine shops, etc. The DBA is not supposed to be the best kept secret of contracting employment.

Conclusion – Don’t Let Employers Profit from Bad Behavior:

A familiar maxim comes to mind: No man may take advantage of his own wrong. See Glus v. Brooklyn E. Dist. Terminal, 359 U.S. 231, 233 (1959) (addressing statute of limitations in Federal Employers’ Liability Act). If an employer knows it is required by law to post notices about an employee’s workers’ compensation rights–which it obviously does since it agreed to adhere to all Longshore Act provisions when it got its government contract–then the employer should not be allowed to avoid the payment of compensation by pleading the statute of limitations. The employer’s failure to post the Form LS-241 hid the existence of the cause of action from injured workers, creating an extraordinary circumstance or external obstacle outside of the workers’ control.

Contracting companies employ thousands of workers from poor countries in the Balkans, Asia, Africa, and South America. They are paid very low wages compared to their U.S. counterparts. The mother tongue for these employees is rarely English. Yet, these people are supposed to know their rights under the Defense Base Act even though their sophisticated and savvy employer refused to conspicuously display the mandated notice explaining the existence of those rights? I don’t think so.

Notice rules exist “to protect and preserve the rights of an injured employee who may be ignorant of the procedures or, indeed, the very existence of workmen’s compensation.” Reynolds v. Workmen’s Comp. Appeals Bd., 12 Cal.3d 726, 729 (Cal. 1974). If equitable tolling is available for other remedial and humanitarian acts–e.g., Title VII, the ADEA, the FLSA–then equitable tolling should be available in Longshore Act and DBA claims, too. Surely an employer’s failure to post a legally required notice of the existence of employee rights fails to accord with the humanitarian purpose of the Longshore Act and DBA. See, e.g., O’Keeffe v. Smith, Hinchman and Grylls Assocs., Inc., 380 U.S. 359, 363 (1965).