An employee’s injury does not have to be caused by a specific traumatic event. Working conditions alone can be sufficient to cause a harm and a compensable disability.

An employee’s injury does not have to be caused by a specific traumatic event. Working conditions alone can be sufficient to cause a harm and a compensable disability.

Some people do not understand the “injurious working conditions” concept. So, let’s start at the beginning: the prima facie case. When a claimant initiates a Longshore or Defense Base Act claim, they must prove two things:

- They suffered some harm or pain; and

- Working conditions existed or an accident occurred which could have caused the harm or pain.

If the claimant successfully proves these two things, then they are entitled to the Section 20(a) presumption. See 33 U.S.C. 920(a) (1984). Affirmative medical evidence is not absolutely necessary, but it is helpful.

The Section 20(a) presumption is a powerful tool. After the prima facie case is proven, the Longshore and Defense Base Acts presume that the worker’s injury falls under the purview of the applicable Act. Further, the presumption puts the onus on the employer to produce substantial evidence–not just “any” evidence–that the injury is not work related. If the employer fails in their burden, then they owe benefits. But if the employer does produce substantial evidence then the fact finder will weigh the evidence that each party submitted. At this point in the case, the injured worker bears the burden of persuading the fact finder and establish that the condition is work-related by a preponderance of the evidence.

Back to the matter at hand: working conditions. Some employers and carriers cannot wrap their mind around the concept that working conditions in and of themselves can cause an compensable injury. To be sure, the injury has to be related to the working conditions.

So what types of “working conditions” have been found compensable? Here are some examples:

- Lifting heavy sheets of metal at work such that a back injury was caused or aggravated. Marinette Marine Corp. v. OWCP, 431 F.3d 1032, 1035 (7th Cir. 2005) (the LHWC does not require that a later injury fundamentally alter a prior condition; it is enough that it produces or contributes to a worsening of symptoms);

- Long hours as a mechanic with lifting, bending, stretching, and working in tight spots for hours on end. Delaware River Stevedores, Inc. v. Dir., OWCP, 279 F.3d 233 (3d Cir. 2002) (holding that “[i]f the conditions of a claimant’s employment cause him to become symptomatic, even if no permanent harm results, the claimant has sustained an injury within the meaning of the Act”).

- Repetitive use of arm at subsequent shoulder that aggravated a rotator cuff tear. Kelaita v. Dir., OWCP, 799 F.2d 1308, 1312 (9th Cir. 1986) (holding employer responsible for the injury because the employee suffered “pain flare-ups . . . related to his work” at the last place of employment).

- Working as a pile butt driver, which included “operating jackhammers, saws, and drills, and carrying large pieces of concrete, lumber and steel.” Foundation Constructors, Inc. v. Dir., OWCP, 950 F.2d 621 (9th Cir. 1991) (“We think that there is adequate evidence for a reasonable mind to conclude that [Claimant’s] last six months of jackhammering and pile driving aggravated his preexisting back injury.”).

- Chest pains from stress at work. Care v. Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Auth., 21 BRBS 248 (1988) (finding that claimant’s chest pains were sufficient to satisfy the “harm” element of his prima facie case; the underlying disease need not be caused by the employment under the aggravation rule; as the medical experts agree claimant’s chest pains were at least in part related to stress in his work, the presumption is not rebutted and claimant’s injury is work-related).

- Workplace harassment, including twenty years of ridicule, insults, and practical jokes. Bath Iron Works Corp. v. Preston, 380 F.3d 597 (1st Cir. 2004) (work place stress led to exacerbation of neurological condition).

But perhaps the best reasoning about injurious working conditions comes from the Ninth Circuit. A last responsible employer dispute developed after the employee suffered an injury during his one, single day of employment. During that day, the employee operated a forklift. Using the gas and brake pedals, and mounting and dismounting the vehicle many times, caused his preexisting knee injury to worsen. The Ninth Circuit determined that one single day of injurious exposure–the cumulative forklift work during his sole day of employment–was enough to aggravate a condition to the point that the worker suffered a compensable injury. Metropolitan Stevedore Co. v. Crescent Wharf and Warehouse Co., 339 F.3d 1102 (9th Cir. 2003).

All things considered, it should not be hard for an employer or carrier to grasp the “working conditions” concept. It is not hard to imagine that a Defense Base Act contractor working 12-hour days, 7 days-per-week in Afghanistan could suffer a back injury as a result of his heavy demand work. Nor is it hard to imagine that a longshoreman might injure their knee or shoulder due to the repetitive loading or unloading of a vessel.

The lack of a traumatic injury should not embolden an employer and carrier to reject a claim for benefits, especially where working conditions existed that could have caused the injured worker’s harm.

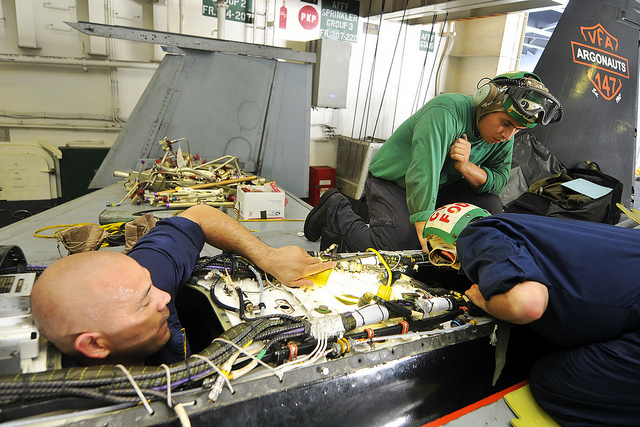

Photo courtesy of Flickr user Official U.S. Navy Page. This photo depicts two civilian contractors working with a seaman to install a fuel cell.