The First Circuit just affirmed an award of death benefits to the widow of an employee killed in a traffic accident in Tbilisi, Georgia. In Battelle Memorial Institute v. DiCecca, the decedent was killed when his taxi was hit head-on by a drunk driver. At the time of the crash, he was traveling in a company-provided taxi to a clean and sanitary grocery store. He did not want flies on his meat.

The First Circuit just affirmed an award of death benefits to the widow of an employee killed in a traffic accident in Tbilisi, Georgia. In Battelle Memorial Institute v. DiCecca, the decedent was killed when his taxi was hit head-on by a drunk driver. At the time of the crash, he was traveling in a company-provided taxi to a clean and sanitary grocery store. He did not want flies on his meat.

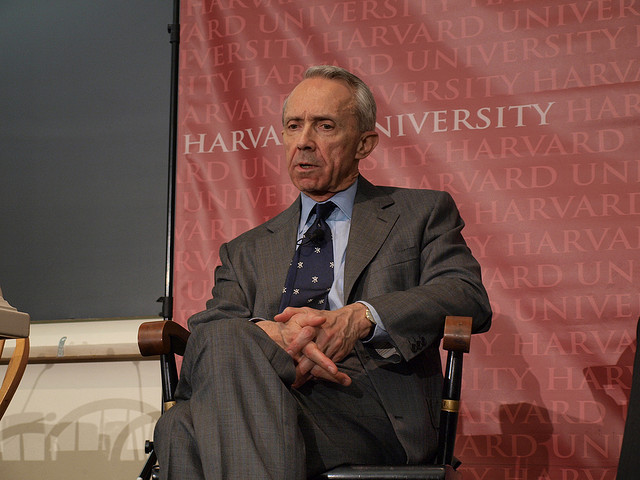

The widow filed a claim for Defense Base Act benefits, which the employer denied. Both the administrative law judge and the Benefits Review Board ruled in the widow’s favor and awarded benefits. In response, the employer petitioned the First Circuit to review and overturn the award. The First Circuit declined to do so, instead affirming the award in a published decision authored by retired Supreme Court Associate Justice David Souter (pictured above).

The Zone of Special Danger in the Supreme Court:

DiCecca is a Defense Base Act case. More importantly, however, is that DiCecca addresses the zone of special danger doctrine. Federal appellate court decisions addressing the zone of special danger doctrine are few and far between. For that reason, the First Circuit discussed the development of the zone of special danger doctrine in three Supreme Court cases: O’Leary, O’Keeffe, and Gondeck. I previously addressed these cases in the DiCecca post I wrote after the oral arguments in March 2015–which predicted a win for the widow.

In O’Leary, an employee died while attempting to rescue two men. The Court rejected a restrictive interpretation of the Defense Base Act, and endorsed the idea of a zone of special danger:

Workmen’s compensation is not confined by common-law conceptions of scope of employment. The test of recovery is not a causal relation between the nature of employment of the injured person and the accident. Nor is it necessary that the employee be engaged at the time of the injury in activity of benefit to his employer. All that is required is that the obligations or conditions of employment create a zone of special danger out of which the injury arose.

See O’Leary v. Brown-Pacific-Maxon, 340 U.S. 504, 507 (1951). Further, the O’Leary Court noted that the zone of special danger inquiry is a “question of fact.” The fact-based application led the First Circuit in DiCecca to note that an “agency’s findings applying the zone-of-special-danger doctrine are commonly reviewed by applying the deferential ‘substantial evidence’ test under the Administrative Procedure Act.”

In O’Keeffe v. Smith, Hinchman & Grylls Associates, Inc., 380 U.S. 359 (1965), the Supreme Court continued to focus on deference to agency determinations, noting that the determination should “stand so long as it is not ‘irrational or unsupported by substantial evidence on the record as a whole.'” As such, it supported the underlying award of benefits. The award was “neither irrational nor wanting substantial evidence.”

Next, in Gondeck v. Pan American World Airways, Inc., 382 U.S. 25 (1965), the Supreme Court again addressed the zone of special danger…and again focused on agency deference. The “limited judicial review” of agency determinations supported the award of benefits under the zone of special danger doctrine.

A Legal Texture, Though Not a Precise Rule:

Justice Souter then distilled the Supreme Court cases (and the few appellate cases on point) to “some general principles creating a legal texture, though not a precise rule.” The general principles include the following:

- The zone of special danger doctrine covers injuries caused by “foreseeable risks occasioned by or associated with the employment abroad,” no matter whether the injury has a “direct causal connection to an employee’s particular job or to any immediate service for the employer.”

- A “special danger” includes risks peculiar to a foreign location; risks of greater magnitude than those encountered domestically; and risks that might occur anywhere but in fact occur where the employee is injured.

- The “special” in “zone of special danger” means “particular” but not necessarily “enhanced.”

- Whether a risk is foreseeable runs on the totality of the circumstances.

- The determining agency is given deference with respect to the application of the zone of special danger. Rational determinations to apply the zone will be upheld. Whether the zone of special danger applies is a finding of fact.

Affirming the Widow’s Defense Base Act Benefits Award:

The First Circuit next addressed the widow’s specific award of benefits. Justice Souter decided to block quote the following determinative paragraph from the Benefits Review Board’s decision, so I am going to do the same:

The administrative law judge addressed the proper inquiry under O’Leary, focusing on the foreseeability of the injury given the conditions and obligations of employment in a dangerous locale. Decedent lived and worked in a dangerous locale as evidenced by the employer’s payment of a hardship allowance/danger pay. Employer provided its employees taxi vouchers each month for use with a specific cab company that utilized Mercedes Benz automobiles. Employer permitted its employees to utilize the cab service for any reason within a certain radius . . . . [I]t is also entirely foreseeable that an employee will need to purchase groceries, and, given the taxi vouchers provided by employer, entirely foreseeable that decedent would take a taxi to the grocery store. The fatal accident, thus, also was a foreseeable, “if not foreseen,” consequence of riding in a taxi in a place where the dangers of automobile travel were anticipated by employer. Although employer attempted to mitigate the danger, employer has not cited any circumstances that would warrant a legal conclusion that decedent’s activity was not rooted in the conditions of his employment or was “thoroughly disconnected” from the service of employer. We, therefore, affirm the administrative law judge’s findings that the zone of special danger doctrine applies and that decedent’s death is compensable under the Act as they are rational, supported by substantial evidence and in accordance with law.

The First Circuit agreed with many of the facts identified by the Benefits Review Board that leaned in favor of application of the zone of special danger doctrine. In fact, the First Circuit appeared to be willing to apply the zone of special danger on fewer facts than identified by the Board. Specifically, and without regard to the hazard pay provision in the employment contract, Justice Souter noted that the following facts would “suffice for liability:”

- The employer assigned decedent to a foreign workplace.

- The decedent was always subject to call.

- The employer provided transportation there by taxi service “limited as to geography but for any purpose.”

- Food buying was foreseeable travel with risks that were realized in this fatal accident.

Further, the First Circuit dismissed the employer’s argument that grocery shopping–a necessity–should not be considered within the scope of employment. At the outset, the decedent’s food buying trip was not a “simple pursuit of necessity” because, as the record demonstrated, the decedent had to buy groceries from the particular store he was traveling to at the time of his injury. And, in any event, “a categorical distinction between pursuit of necessity and optional engagement in recreation would be irrational.”

Moreover, there is no heightened danger requirement for application of the zone of special danger. The employer had asked the First Circuit to limit the zone of special danger to a “binary” application. The zone would only apply to injuries occurring during “reasonable recreation” or injuries occurring at locales with heightened danger. Justice Souter noted that the case law did not support the distinction urged by the employer:

What does not follow, however, is that good times are the only foreign activities that serve the employer as well as the employee, or even that mutual benefit is necessary for an adequate nexus in the absence of enhanced risk. To begin with, these cases cannot be reduced to a single controlling factor, for in each case, the application of the zone-of-special-danger doctrine turned on the totality of circumstances. And, even if these cases could be reduced to a single crux, it would not be employer benefit, which was flatly rejected in O’Leary. What is more, even if employer benefit were crucial, it is hard to imagine a better example of an activity that benefits the employer than its employee’s pursuit of safe food to stay alive and healthy; flies on the meat are to be avoided. And, finally, to the extent that geographic isolation in a foreign venue appears to be doing any work in the case law, it explains why an otherwise personal activity, like recreation, should be deemed a necessity and thus incident to overseas employment. By that logic, because grocery shopping is a necessity, it too should be considered an incident to the employment. The short of it is that it is very hard, perhaps impossible, to distill a rule that injuries arising out of a night on the town are covered but not those incurred shopping for food.

Weaving Its Way Into the Legal Texture:

This is most likely the most important Defense Base Act case of the year. DiCecca will undoubtedly weave its way into the “legal texture,” creating guideposts on what would seem to be an otherwise easily navigable road. I expect to see employers and carriers refrain from their categorical “necessity v. recreation” arguments. I also expect to see more deference given to administrative law judge decisions, perhaps resulting in fewer appeals. All the same, I do expect there to be a more in-depth inquiry into the facts and circumstances surrounding the obligations and conditions of an injured worker’s employment to satisfy the “totality of the circumstances” inquiry. Further, I found it interesting that Justice Souter would have assigned liability even without the benefit of the hazard pay provision in the decedent’s contract. In future cases, perhaps hazard pay will be considered lagniappe for an otherwise compensable claim.

Finally, a word about precedent. DiCecca is only precedential in cases arising in the First Circuit’s jurisdiction. Nonetheless, a retired Associate Justice from the Supreme Court wrote the DiCecca decision. My guess is that many future courts will find DiCecca persuasive, thus taking the same approach to similar zone of special danger cases.

Photograph of Justice Souter courtesy of Flickr user Harvard Law Record.