The value of a Defense Base Act death benefits claim depends on the life expectancy of the claimant. The shorter the life expectancy, the cheaper the claim.

So what happens when a claimant’s life expectancy is cut short because of an unannounced change in government policy? Foreign nationals are about to find out because the Division of Longshore and Harbor Workers’ Compensation (DLHWC) just announced a new policy that reduces the presumed life expectancy for some claimants by 20 years or more.

The new life expectancy change will affect commutation claims by foreign national beneficiaries–mostly death claims from spouses, elderly parents, and children. Here, I discuss commutation, the new life expectancy tables used by DLHWC, and the real-world effect of the life expectancy change on the value of a Defense Base Act claim. I also propose a solution: a rebuttable presumption whereby the Defense Base Act claimant can establish that the World Health Organization life table does not accurately predict their individual life expectancy.

What is Commutation?

The Defense Base Act applies to foreign nationals. If an employee is injured, they get workers’ compensation coverage no matter their nationality. See 33 U.S.C. § 908. If an employee is killed, then qualified beneficiaries may receive death benefits. See 33 U.S.C. § 909; see also 42 U.S.C. § 1652. But there are some important differences for death benefits and permanent total disability claims involving foreign nationals. One of those differences is called “commutation.”

“Commutation” is the process for determining the value of a lump sum benefits payout to certain qualifying Defense Base Act claimants. Typically, commutation claims involve surviving widows, children, and parents receiving death benefits. A carrier can request the Secretary of Labor to “commute” the future installments of compensation due for death benefits or permanent total disability. When this happens, the carrier sends a list of written stipulations to DLHWC with supporting evidence for each stipulation. The stipulations address the decedent’s employment, average weekly wage, compensation rate, cause of death, biographical information about the surviving beneficiaries, and any other claim-specific information that DLHWC may need to review. DLHWC then takes all of this information and calculates a lump sum owed to the beneficiaries. The catch is that the amount paid to the beneficiaries is reduced by 50%. See 42 U.S.C. § 1652; see also 20 C.F.R. §§ 702.142, 704.102.

How is Commutation Changing?

On March 23, 2015, DLHWC changed how it calculated the life expectancy of foreign nationals. Before March 23, 2015, DLHWC used life tables developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for United States citizens. No matter where the beneficiary lived, DLHWC presumed that the beneficiary would have the same life expectancy as a resident of the United States. Now, DLHWC will use the country-specific life tables created by the World Health Organization.

DLHWC announced the change in Transmittal No. 15-01. The most important change mentioned in the Transmittal (with emphasis added in bold) is printed below:

The statute and regulations provide the Director broad discretion in calculating commutation amounts. They do not mandate any particular method of calculation or dictate any particular formula. Rather, the statute permits commutation calculations to be made in an amount “as determined by the Secretary” without imposing any limitations or conditions. The Director is therefore authorized to calculate commutations using whatever method he deems appropriate. Exercising this discretion, the Director has determined that as of the date of this transmittal, the DLHWC will begin calculating life expectancy using the beneficiary’s country of residence and the tables developed by the World Health Organization (WHO).

Historically, the DLHWC used the United States Life Tables produced by the United States Department of Health and Human Services for commutation calculations. However, under current law, commutation is only available for non-United States citizens who are not United States residents; all claimants/beneficiaries affected do not live in the United States. Conditions that lead to longevity in the United States may not be present in other countries, and life expectancy tables specific to the United States are not necessarily the best indicator of life expectancy in foreign countries. This is especially true when credible, country-specific life tables exist that are readily accessible on-line, thereby providing transparency, and are an accurate alternative.

The DLHWC considers the WHO to be a credible source of information for country specific life expectancy.

What Has Really Changed?

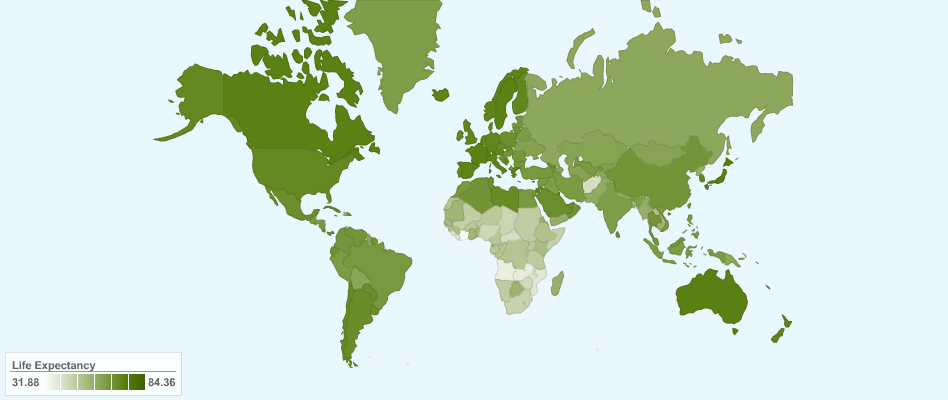

Does a change in life tables really make that much of a difference? Yes, actually. The benefits owed to a foreign national from poorer, underdeveloped country will decrease sharply because the World Health Organization assigns lower life expectancies to many of those countries.

Until now, the life table used by DLHWC assumed that men would live 75.4 years and women would live 80.4 years. Every foreign beneficiary, no matter where they resided, were given this life expectancy.

Now, life expectancy is determined by country of residence. The World Health Organization’s life tables provide vital statistics for each country. For instance, these are the life expectancies for foreign nationals in Afghanistan, Fiji, Iraq, Nepal, Philippines, South Africa, and Uganda.

- Afghanistan: men live 58 years and women live 61 years.

- Fiji: men live 67 years and women live 73 years.

- Iraq: men live 66 years and women live 74 years.

- Nepal: men live 67 years and women live 69 years.

- Philippines: men live 65 years and women live 72 years.

- South Africa: men live 56 years and women live 62 years.

- Uganda: men live 56 years and women live 58 years.

To be fair, there are countries with a longer life expectancy. Foreign nationals in the following countries may be entitled to more compensation than before the change:

- Australia: men live 81 years and women live 85 years.

- Belgium: men live 78 years and women live 83 years.

- New Zealand: men live 80 years and women live 84 years.

- United Kingdom: men live 79 years and women live 83 years.

Who Will This Affect?

For the most part, this change will affect two classes of foreign beneficiaries: spouses and parents from poorer countries. The Defense Base Act requires employers and carriers to pay death benefits to a spouse at the rate of 50% of the decedent’s average weekly wage. Benefits are paid on an ongoing bases. They only stop upon the surviving spouse’s remarriage or death. Financially dependent parents receive 25% of the decedent’s average weekly wage. Typically, benefits are paid until death.

When a carrier requests commutation for a death benefits case, DLHWC calculates a lifetime of benefits. With the new World Health Organization life tables, that lifetime is much shorter than it used to be.

Just consider three examples demonstrating the changes that will affect some Defense Base Act widows. First, a South African widow:

Decedent was a South African employee earning $2,000 per week while working in Afghanistan. He left behind a 40-year-old widow, also from South Africa. At the time of the decedent’s death, the widow’s initial benefit rate was $1,000 per week, subject to annual cost of living adjustments. To arrive at the commutation value, DLHWC would use the widow’s life expectancy, her compensation rate, the National Average Weekly Wage percent increase, and the one year constant maturity rate as of the date that DLHWC performed the calculations. For this hypothetical, assume that the National Average Weekly wage percent increase equals 2.25% and the one year constant maturity rate equals 0.28%.

Under the old system, the South African widow would be presumed to have a 40 year life expectancy. According to DLHWC’s commutation calculator, the dollar value of her commutation claim was roughly $1,760,000.00.

Under the new system, where the World Health Organization’s life table is used, the South African widow will be presumed to have a 22-year life expectancy. Using the same calculator, the dollar value of the widow’s commutation claim is roughly $750,000.00.

Next, an Iraqi widow:

Decedent was an Iraqi employee earning $200 per week while working in Iraq, his home country. He left behind a 40-year-old widow, also from Iraq. At the time of the decedent’s death, the widow’s initial benefit rate was $100 per week, subject to annual cost of living adjustments. To arrive at the commutation value, DLHWC would use the widow’s life expectancy, her compensation rate, the National Average Weekly Wage percent increase, and the one year constant maturity rate as of the date that DLHWC performed the calculations. For this hypothetical, assume that the National Average Weekly wage percent increase equals 2.25% and the one year constant maturity rate equals 0.28%.

Under the old system, the Iraqi widow would be presumed to have a 40 year life expectancy. According to DLHWC’s commutation calculator, the dollar value of her commutation claim was approximately $176,000.00.

Under the new system, where the World Health Organization’s life table is used, the Iraqi widow will be presumed to have a 34-year life expectancy. Using the same calculator, the dollar value of the widow’s commutation claim is approximately $131,000.00.

Finally, an Australian widow. In this situation, the widow’s claim is worth more now that DLHWC uses the World Health Organization life tables.

Decedent was an Australian employee earning $3,000 per week while working in Afghanistan. He left behind a 40-year-old widow, also from Australia. At the time of the decedent’s death, the widow’s initial benefit rate equaled the statutory maximum rate allowed by law: $1,346.68 per week, subject to annual cost of living adjustments. To arrive at the commutation value, DLHWC would use the widow’s life expectancy, her compensation rate, the National Average Weekly Wage percent increase, and the one year constant maturity rate as of the date that DLHWC performed the calculations. For this hypothetical, assume that the National Average Weekly wage percent increase equals 2.25% and the one year constant maturity rate equals 0.28%.

Under the old system, the Australian widow would be presumed to have a 40 year life expectancy. According to DLHWC’s commutation calculator, the dollar value of her commutation claim was roughly $2,285,000.00.

Under the new system, where the WHO’s life table is used, the Australian widow will be presumed to have a 45-year life expectancy. Using the same calculator, the dollar value of the widow’s commutation claim was roughly $2,530.000.00.

These examples demonstrate the difference a day–and a new government policy–makes.

Why Not Use a Rebuttable Presumption?

I would like to see DLHWC soften its position regarding life tables for commutation claims. Instead of issuing an edict–thou shalt use World Health Organization life expectancy tables–why not make the life tables a rebuttable presumption of the length of a foreign national’s life expectancy? In other words, give claimants an opportunity to prove why the World Health Organization life tables should not apply to them.

I would like to see DLHWC soften its position regarding life tables for commutation claims. Instead of issuing an edict–thou shalt use World Health Organization life expectancy tables–why not make the life tables a rebuttable presumption of the length of a foreign national’s life expectancy? In other words, give claimants an opportunity to prove why the World Health Organization life tables should not apply to them.

Transmittal No. 15-01 cites the Director’s broad statutory and regulatory power with respect to commutations. If the Director’s power is broad enough to reduce the commutation value for widows and parents from poor countries with a mere Transmittal Notice, then surely it is broad enough to give claimants or their representatives an opportunity to show why the World Health Organization tables should not apply to their case. In the absence of statutes or regulations mandating the “particular method of calculation” for commutation claims, there is no reason why the Director could not provide a rebuttable presumption.

I understand the carrier’s concern with using CDC life tables developed for U.S. citizens to determine the life expectancy of foreign nationals. The dollar value of a commutation calculation based on CDC life tables results in a financial windfall to some foreign nationals–sometimes to the tune of hundreds of thousands of dollars. The concern is valid.

But sometimes life expectancy tables fail to provide an accurate prognostication of a particular claimant’s longevity.

If a change in life expectancy tables must occur, then couple that change with a rebuttable presumption. A rebuttable presumption respects the concerns of carriers while simultaneously providing claimants with an opportunity to demonstrate the deficiencies of the World Health Organization’s life expectancy tables as applied to their individual case.

Here are some of the problems and questions that could develop with DLHWC’s use of the World Health Organization life expectancy tables:

- Sometimes life tables use both race and gender to calculate a particular individual’s life expectancy. Just look at the CDC’s United States Life Tables for 2010, which provides separate life expectancy calculations for black, hispanic, and white populations in the United States. The World Health Organization tables referenced by DLHWC in Transmittal No. 15-01 provide separate life expectancies for men and women, with women typically living longer than men. So, we know that DLHWC calculates different life expectancies based on gender. But will it also calculate a different life expectancy for a foreign national based on race? What about countries like South Africa where it is a true and unfortunate fact that there is a tremendous disparity in the life expectancy of black and white South Africans?

- The World Health Organization’s life tables may not be calculated with the most up-to-date information. Instead of the WHO tables, give claimants an opportunity to provide newer life expectancy tables created by the government of their country of residence. Again, I will use South Africa as an example. According to this information, the life expectancy of the total population at birth for 2014 is 59.1 years for males and 63.1 years for females. This is higher than the WHO’s estimates. Plus, use of a country-specific life table developed by the government for the country in which the beneficiary resides will promote the same goals identified in Transmittal No. 15-01: transparency, accuracy, and a credible assessment of the conditions affecting longevity in the country of residence.

- DLHWC used to require stipulations signed by both the employer/carrier and the claimant before it would process a commutation. If this is still a requirement, then the change in life expectancy tables will cause some claimants to refuse to sign stipulations, thus delaying the resolution of their claim.

- DLHWC has announced that it will use the World Health Organization life expectancy tables, but should there also be an affirmative duty to identify the claimant’s life expectancy in the stipulations that the employer/carrier wants the claimant to sign? DLHWC’s Transmittal Notice lauds the easy online accessibility of the WHO life tables, but the ease with which a Washington, D.C.-based government agency or a multinational insurance carrier accesses the Internet may not be shared by the claimants who will be hit hardest by the change in life tables. This problem could be cured by including the life expectancy in the stipulation.

- Life expectancy tables are also used in Defense Base Act settlements–for all claims, no matter the claimant’s country of residence. Does this new change in life tables apply to other resolution options, like settlements? Unlike commutations, there are very specific statutory and regulatory requirements for settlements. Above all else, settlements must be adequate. But will DLHWC measure the adequacy of a foreign national’s settlement against CDC life tables or WHO life tables?

Conclusion:

The change in life expectancy tables is troubling. Without any fanfare and with very little forewarning, DLHWC made a significant change that will negatively affect a significant number of claimants. Let’s not forget who DLHWC’s decision hurts: widows and parents from countries plagued with poverty, infectious diseases of epidemic proportions, and woefully deficient healthcare. At the same time, carriers have legitimate concerns that the prior system–assuming a U.S. life expectancy despite the claimant’s country of residence–produced financial windfalls to claimants who have a lower life expectancy than U.S. citizens and residents.

I am fine with finding a middle ground that respects the interests of both claimants and carriers. But perhaps the World Health Organization life expectancy tables should be the first step, not the last step, on the path to fairness. Give foreign national claimants the opportunity to rebut the presumption that the WHO tables accurately predict their individual life expectancy.

Attributions:

Life expectancy map courtesy of Flickr user Thiagarajan Vardharaju.

World Health Organization Logo courtesy of Flickr user United States Mission Geneva.

United States and South African flags photo courtesy of Flickr user GovernmentZA.

Announcement:

Strongpoint Law Firm accepts Defense Base Act claims worldwide. If you need assistance with a Defense Base Act claim, contact Strongpoint Law Firm and Jon Robinson immediately for a free case evaluation. Strongpoint Law Firm can be reached at (985) 246-3194, online at www.strongpointlaw.com, and via e-mail at [email protected].